Personal Science and the Quantified Self Guru

Btihaj Ajana (King’s College London)

This is the submitted version of the chapter.

Cite as:

Ajana, B. (2022) ‘Personal Science and the Quantified Self Guru’. In Lawrence, S. (ed.) Digital Wellness, Health and Fitness Influencers: Critical Perspectives on Digital Guru Media. London: Routledge.

Abstract

In this chapter, I examine the ways in which Quantified Self practices can be considered as “personal science,” a term first introduced by Martin and Brouwer in early 1990s and recently adopted by the Quantified Self community to describe its self-tracking activities and objectives. In doing so, I revisit some relevant arguments put forward by the philosopher, Hans-Georg Gadamer, vis-à-vis the value of the personal and hermeneutic dimension to understanding aspects of health and appreciating the limits of traditional medical methods and their generalising approach. After laying down the basis of the Quantified Self as personal science, the chapter proceeds to examine the example of the Danish self-tracker, Thomas Blomseth Christiansen, who is famous for curing himself of his severe allergies thanks to tracking his sneezes since 2011 and monitoring various other bodily and environmental variables. By drawing on interviews I conducted with Thomas and weaving them into relevant philosophical debates, I provide a critical discussion on the way self-tracking can be seen, at once, as a way of reclaiming autonomy and control over one’s health as well as a form of outsourcing decision-making to technology itself. This discussion leads me to differentiate between active and passive self-tracking, and between members of the Quantified Self circle who build their own tools and the general users who rely on the commercial tech solutions available on the market. Ultimately, I suggest that the Quantified Self community can act as a “guru” for mainstream self-trackers by nurturing a critical and inclusive approach to technological development and use, which can enable users to be involved in the means of production and become experts rather than just users.

Keywords

Personal Science, Quantified Self, Self-tracking, Autonomy, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Thomas Blomseth Christiansen

Introduction

Human beings have long been interested in exploring and understanding themselves through available technologies and techniques. From oral and text-based practices of confession, journaling and psychoanalysis to contemporary digital forms of lifelogging and self-tracking, the hunt for self-knowledge continues to be major pursuit for humanity. While methods of self-enquiry have been shaped by the technological developments du jour, the epistemic interest in the self per se is very much a product of culture itself and the growing emphasis on self-improvement and personal development. As Jethani and Raydan (2015: 78) note, much of the gravitas of society’s current preoccupation with knowledge of the self comes from popular culture, lifestyle marketing and the belief that self-knowledge necessarily leads to self-betterment, an ideology that has long been espoused by religion, science, and the self-help industry alike.

The Quantified Self movement is the latest chapter in the history of self-enquiry which seeks to harness the power of technological innovations for the purpose of self-knowledge and self-improvement. More than a type of self-help, the Quantified Self is a lifestyle that is embraced by a growing number of people around the world who are interested in self-experimentation, activity tracking and body hacking, using sensor technology and personal data analytics. The term itself is attributed to Wired magazine editors, Kevin Kelly and Gary Wolf, who used it in 2007 as a name for a small gathering of technologists and users interested in incorporating digital technologies and wearable sensors to collect, log and analyse data regarding their everyday activities, behaviours, habits and vital signs. Since then, interest grew and the stream of media articles about the movement, together with popular TED talks and high-profile conferences and symposia, helped increase public awareness of the movement and its practices, turning it into a global phenomenon with many affiliated Meetup groups worldwide whose shared interest is “self-knowledge through numbers.” While the Quantified Self is still a relatively niche community with officially 95,845 members at the time of writing this chapter, its data-driven practices and pragmatic philosophy have nonetheless become widespread beyond the community itself, since they befit the highly digital world we live in and the increasing fondness for wearable technology and datafied forms of self-analysis and health monitoring. There remains however a crucial difference between the experimental and “serious” nature of the Quantified Self fundamentals and the recreational self-tracking practices embraced by the general public. As Heyen (2020) observes, Quantified Self followers ‘develop personal epistemic goals and pursue these by specific self-tracking activities that resemble research.’ Also, while everyday users of self-tracking technologies are mostly reliant on commercial products, such as Fitbit Charge, Garmin Vivosport, Amazfit Bip and Apple Watch, to track their activities and quantify their bodies, many members of the Quantified Self tend to build their own tracking tools and data storage solutions to avoid relying on commercially available devices and apps. This has implications on the epistemic as well as methodological dimensions of the Quantified Self practices, and on the way this community deals with issues of data ownership and privacy, as we shall discuss later on.

Much has been written about the Quantified Self over the last decade so much so that one might wonder if there is anything more left to say about this movement and its practices. Such question was, in fact, directed at me by a couple of academic participants at a recent symposium where I presented a paper on the data sharing culture using the Quantified Self as a case study. After delivering my talk, the two participants approached me and said: “Oh, you are still working on the Quantified Self!?!.” As benign as their statement might be, it is indeed reflective of a notable declining interest in the Quantified Self movement itself over the last three years , even though self-tracking practices are becoming more and more embedded in everyday life and products. In fact, it might be because self-tracking has become so normalised and a ubiquitous feature of our lives that academic (and commercial) interest is starting to detract from what was once perceived as a novel phenomenon and a unique community of practice. But this, in my opinion, should not diminish one’s curiosity about the movement. On the contrary, it is now more important than ever to examine what has been learnt in the last decade of the movement’s life and its likely future trajectory, and reflect on the ways in which the specialised practices of the Quantified Self community can shape the politics and ethics of mainstream tracking practices that are facilitated by commercial devices and platforms.

Like many socio-technical movements and communities of practice, the Quantified Self has gone through its own configurations and changes. Some of these have to do with shifts in interests and focus, while others relate to developments in tracking technologies themselves as well as the recent outbreak of coronavirus which called for new forms of tracking and body quantification. Of particular interest to this chapter is the recent re-orientation of the Quantified Self movement towards the notion of “personal science” whose focus is to engage with health-related issues and questions that medicine itself does not often address with its one-size-fits-all dominant approach.

As such, the next section of the chapter is dedicated to examining the link between self-tracking practices and personal science, a term first introduced by Martin and Brouwer in early 1990s to emphasise the importance of personal knowledge and narratives dimensions in science. The section begins by looking at a conceptual framework recently introduced by Gary Wolf and Martijn De Groot (2020) as well as relevant arguments put forward by the philosopher, Hans-Georg Gadamer, vis-à-vis the value of the personal and hermeneutic dimension to understanding aspects of health and appreciating the limits of traditional medical methods.

After laying down the basis of the Quantified Self as personal science, the next section of the chapter proceeds to examine the example of the Danish self-tracker, Thomas Blomseth Christiansen, who is famous for curing himself of his severe allergies thanks to tracking his sneezes since 2011 and monitoring various other bodily and environmental variables. By drawing on interviews I conducted with Thomas and weaving them into relevant philosophical debates, I provide a critical discussion on the way self-tracking can be seen, at once, as a way of reclaiming autonomy and control over one’s health as well as a form of outsourcing decision-making to technology itself. This discussion leads me to differentiate between active and passive self-tracking, and between members of the Quantified Self circle who build their own tracking tools and the general users who rely on the commercial tech solutions available on the market. Ultimately, I suggest that the Quantified Self community can act as a “guru” for mainstream self-trackers by nurturing a critical and inclusive approach to technological development and use, beyond the confines of the community itself, which can enable users to be involved in the means of production and become experts rather than just users.

Personal Science

In a recent article, Gary Wolf and Martijn De Groot (2020) introduce a conceptual framework for personal science which they define as using empirical methods to pursue personal health questions. At the same time, they describe the similarities and differences between personal science, citizen science and single subject (N-of-1) research in medicine. Whereas citizen science and single subject research have traditionally been aimed at contributing data to mainstream institutional science with the ultimate goal of creating ‘generalisable knowledge’ (though some of these practices can also take place outside institutional settings), personal science, on the other hand, is highly individual. It focuses on ‘long term personal challenges and questions such as finding the triggers of intermittent conditions in everyday life, understanding the effects of changes in diet and daily activities on physical and mental health, or using regular measurements to guide day-to-day decision making about sports, travel, work, and management of chronic disease.’ (Wolf and De Groot, 2020: 3). In this sense, the questions in personal science are determined by personal motives alone, whereas in citizen science and N-of-1 research, the questions are usually determined by the research agenda of the scientific discipline (ibid.: 4).

Drawing on some of the examples of Quantified Self practices and self-enquiries, Wolf and De Groot identify five kinds of activities that characterise such practices from which the authors derive the conceptual framework for personal science. These activities are questioning, designing, observing, reasoning, and discovering. Similar to any form of research, personal science, as exemplified by Quantified Self practices, begins by posing questions, and in this case, questions that are relevant to the individual herself. As the authors explain, it is ‘the self-reflexive quality of the questions that makes personal science personal; that is, the researcher’s own life is the research domain.’ (Wolf and De Groot, 2020: 2). What follows is the design process which involves exploring, applying, adapting and experimenting with relevant empirical methods to suit one’s aims and personal enquiry. As mentioned before, members of the Quantified Self community have been very active in developing tools and methods of tracking and data analysis. The collection of self-tracking data allows observations to be made about one’s own health, habits and lifestyle. Observations can be gathered through analogue methods such as journaling and handwritten notes or via digital means through sensor devices and apps that allow the collection of various data relating to individual activities, vital signs, environmental factors, emotional state, and so on. The gathered data are then explored, analysed and, often, visualised as part of the reasoning process which can involve not only the individual conducting the self-research but also peers who can provide feedback, guidance and suggestions. This is, in fact, a crucial aspect of the Quantified Self community. Although the ‘self’ is the main emphasis of the Quantified Self and personal science is primarily about the individual, there is, nonetheless, a communal aspect to self-tracking practices, encouraged and facilitated by the Quantified Self community (Ajana, 2017; 2020). As Wolf (2010) argues ‘[p]ersonal data are ideally suited to a social life of sharing. You might not always have something to say, but you always have a number to report.’ Through online and face-to-face channels including a dedicated website and forums, conferences and public symposia, and “Show and Tell” presentations, members of the Quantified Self can share information about their self-tracking experiments and personal journey, discuss their questions, methods and conclusions with one another, and derive useful lessons and conclusions from the process. In this sense, reasoning becomes ‘co-reasoning’. The final activity, discovering, is indeed a product of the whole cycle, as each step of the process can lead to gaining insights and developing skills. Importantly, the essence of the Quantified Self is to act on the insights gained in order to improve one’s everyday life. Collecting self-tracking data is, as such, not an end in itself but a means to take meaningful positive actions and acquire more agency and control of one’s health.

The concept of personal science is not a recent invention by Wolf and De Groot but was introduced back in the early 1990s by Martin and Brower who emphasise that ‘science is not simply rational and objective but that the inquiring person is an integral part of the enquiry.’ (Martin and Brower, 1993: 458). The authors use Polanyi’s concepts of personal knowledge, indwelling, tacit knowledge, commitment, and objectivity to develop their arguments vis-à-vis personal science and the importance of subjective dimensions in scientific practice. They use the term personal science to distinguish ‘the aesthetic and motivational aspects of science—as they apply to individuals from other dimensions of science (methodological, historical, etc.)’ (Martin and Brower, 1991: 714). Crucial to their arguments is the idea that science straddles two modes of thinking, namely the paradigmatic and narrative modes. The paradigmatic mode deploys tools of mathematics and logic and can be identified with the traditional empiricist/rationalist tradition of Western science. On the other hand, the narrative mode seeks to evoke meaning trough stories and interpretations, thereby helping to make sense of the paradigmatic mode (Martin and Brower, 1993: 441).

Martin’s and Brower’s definition and conceptualisation of personal science resonate, indeed, with the characteristics of Quantified Self practices. For not only do such practices follow methods of traditional science to obtain data and produce knowledge, but they also seek to make sense of the tracking journey and data, and produce meaning through the interpretation and visualisation of data as well as the sharing of feedback and tracking experiences among members of the Quantified Self community. Self-tracking involves both the paradigmatic and narrative modes, the quantitative and the qualitative aspects. And, as mentioned before, self-tracking practices are ‘personal’ as they are performed in response to the self-tracker’s personal needs and desire to analyse one’s own body and life. Relatedly, Heyen (2020: 131) argues that Quantified Self practices can also be considered as a form of expertise, or more specifically non-certified expertise since it is not recognised officially by any social institution—although there are doctors, for instance, who are interested in their patient-generated self-tracking data and believe in the co-existence of ‘validated clinical knowledge’ with ‘patient discovery and new forms of therapeutic alliance’ (Prias, 2019: 605).

Long before the introduction of the concept of personal science or the rise of Quantified Self, philosophers such as Gadamer and Canguilhem have already sought to foreground the importance of the personal dimension to science and medicine, challenging the orthodoxy of traditional scientific knowledge and the reductionist methods of rationalist systems. In his book, The Enigma of Health, Gadamer (1996) contends that there are limits to what medicine and science can measure which in turn calls for the hermeneutic perspective, that is to say, the task of subjective interpretation. He writes,

“‘There is no doubt that all our knowledge begins with experience.’ This famous beginning of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason surely holds too for the knowledge we possess of human beings. To begin with this includes the sum total of the ever progressing results of natural scientific research, which we call ‘Science’. But then there is the empirical knowledge of so-called practice that everyone accumulates in the midst of life […] Not only in the professional sphere but also in everyone’s private and personal existence the experience that people develop out of the encounter with themselves and their fellow human beings continually grows […] To be sure, such knowledge is ‘subjective’, that is, largely unverifiable and unstable. It is, nevertheless, knowledge that science cannot ignore.” (Gadamer, 1996: 1)

Referring to the domain of medical care, Gadamer goes to the extent to suggest that, if there is any form of measurement, this can only be a subjective internal measurement felt through the symbiotic relation of the body with the individual’s own states of mind (see also Ajana, Braga and Guidi, forthcoming). This is insofar as conventional scientific measurements do not always manage to cover the true states of somatic equilibrium, which according to Gadamer, obey a kind of natural measure or balance inherent to the body itself and which is not easily amenable to translation into numerical systems. This is why, for Gadamer, health remains an enigma and a mystery whose character is manifest in rhythmic processes of existence such as breathing, sleeping and digesting: ‘the harmony which remains hidden is mightier than the harmony which is revealed [… Health] is a miraculous example of such strong but concealed harmony.’ (Gadamer in Dallmayr, 2000: 333). And as Keane (2015: 64) puts it, ‘for Gadamer […] health is the appropriate balance of bodily forces; it is proportion and balance. The concepts of “proportion” and “balance,” as well as the “more” or “less,” are closely tied up with the concept of “measure,” or, more precisely, with appropriate measure.’ But this measure is not to be understood merely in terms of the instrumental and calculative approach of science. Rather, measure, in Gadamer’s sense, is ‘an open and self-reflexive living through’ which is ‘accessible only by means of a qualitative lived measuring’ (ibid.: 65, emphasis added). Health, as such, ‘exceeds the confines of modern science with correlation of cause and effect’ (Dallmayr, 2000: 334). Being sick and feeling sick are, consequently, two different states. Likewise, George Canguilhem (1991) believes that it is the patient’s perspective that defines the experience of being sick. He argues that ‘medicine always exists de jure, if not de facto, because there are men who feel sick, not because there are doctors to tell men of their illnesses […] Health is life lived in the silence of the organs’ (Canguilhem in Diaz-Bone 2021: 295).

Both Gadamer’s and Canguilhem’s arguments gesture towards the importance of the individual/patient rather than only science and medical expertise in defining what health and sickness are in the first place, a standpoint that is at the heart of contemporary movements such as the Quantified Self, biohacking and personal science whose primary aim is to regain individual autonomy and reclaim agency from the clatch of medical expertise and its “one size fits all” paradigm. Although Quantified Self practices are primarily about the quantification of vital functions and the extraction of data from the body and its activities, the hermeneutic aspect of data interpretation and visualisation is precisely what gives these practices meaning and significance. The convergence of numbers and narrative is what allows the self-tracker to take action with regard to health and lifestyle in accordance with the interpretations derived from data processing and analysis. Without interpretation, data remain merely an empty signifier. The ‘interpretive knowledge’ is just as important as the ‘numerical knowledge’ of the self-tracking experience. And to follow Gadamer’s line of reasoning, measurement practices cannot reveal the hidden dynamics of health and physiological phenomena by simply resorting to quantification qua quantification, but it is the qualitative, experiential, personal and lived dimension of quantification that can lead to gaining insights and producing knowledge about the body, health and wellbeing. Seen in this light, personal science, and with it the Quantified Self, ought to be understood as a combination of quantitative and qualitative dimensions that are irreducible to ‘self-knowledge through numbers;’ the main slogan of the Quantified Self movement itself. In fact, this slogan does not do justice to the nuanced, multi-layered and qualitative aspects of self-tracking practices. At the same time, Quantified Self practices cannot be seen merely as a symptom of an increasing ‘scientification of society’ (Heyen, 2020: 134) nor simply as a manifestation of an increasing ‘metrification of society’ (Ajana 2018; Mau, 2019) tout court. They are also, and as mentioned at the outset, a reflection of a growing cultural emphasis on self-reflexivity, self-development and self-actualisation, aspirations that are hallmarks of late-modernity (Giddens, 1991). Personal Science does indeed capture these different, but interrelated, tropes and socio-technical developments.

Having laid out the basis of the Quantified Self as personal science, I shall proceed now to examine the example of a prominent and dedicated member of the Quantified Self community from Denmark, Thomas Blomseth Christiansen, whose practices provide a case in a point for some of what has been discussed hitherto.

Self-tracking as Personal Science: The Case of Thomas Blomseth Christiansen

In this section, I discuss the self-tracking experience of Thomas based on an in-depth interview I conducted with him in February 2021. I also draw on an earlier interview from 2017 I conducted with him as part of the making of a 13-mins documentary film entitled, Quantified Life (Ajana, 2017) , which explores the practices as well as ethical and political implications pertaining to the growing trend of self-tracking and quantification. Revisiting Thomas’ experience four years after I first encountered him in 2017 has enabled me to gain insights into how his self-tracking journey has evolved over the years. By extension, this also helped me understand the changes and recent developments in the Quantified Self movement, given Thomas’ active involvement in this community of practice and his knowledge of its inner workings.

Thomas began his self-tracking journey in 2007 with the aim to find solutions to his allergies, including pollen allergy, eczema and gut problems. As a software engineer, Thomas believes in system thinking and a data-driven approach to problem solving which he has been applying to his own body in the pursuit of ridding himself of his allergies and improving his overall health: ‘I started turning the methods I know from software development and from process improvement onto myself, and looking at myself as a system that I could improve. To be able to do that, I needed some data, and that was where the self-tracking started.’ (Thomas interview, 2017).

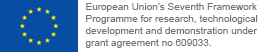

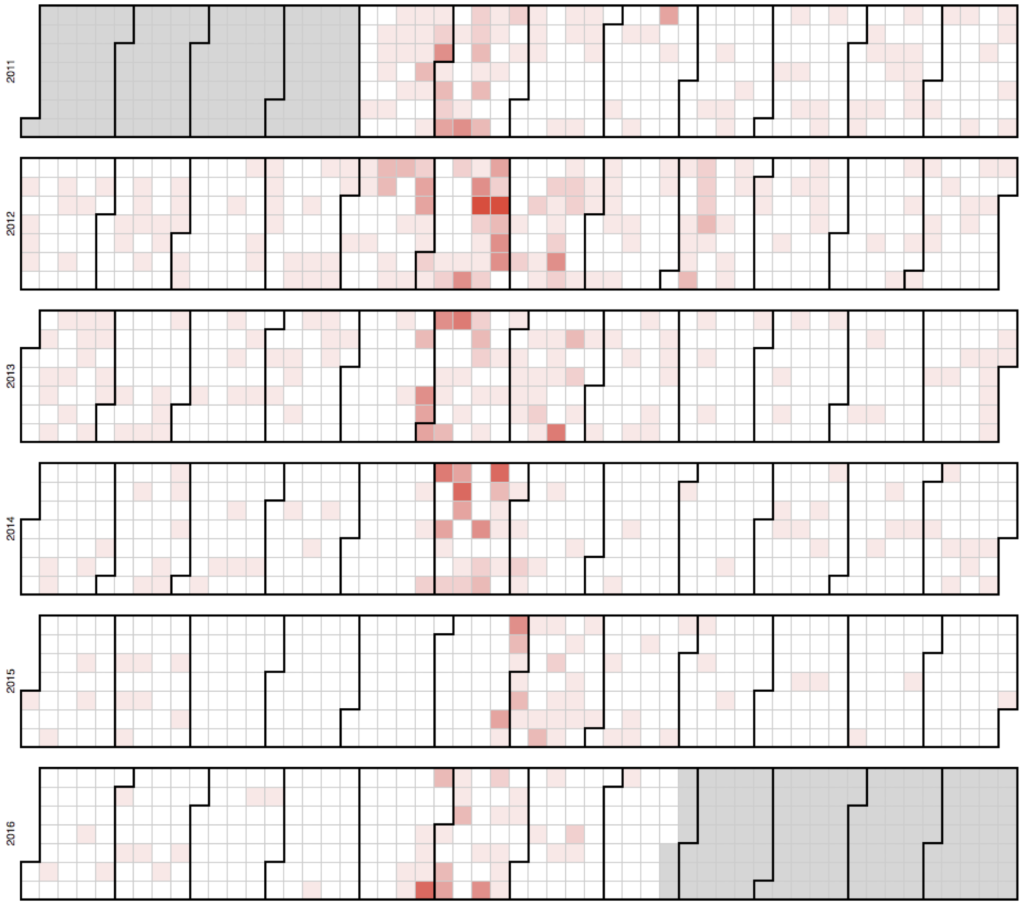

Since then, Thomas has been religiously tracking various aspects and phenomena relating to his body, lifestyle and environment. He made over 110,000 observations over the years from tracking his food and water intake, sleep and fatigue, health supplements, toilet visits, pollen count, and so on (fig.1, fig.2). But, as he puts it, his “claim to fame” is the tracking of his sneezes. He has a complete record of his sneezes since 2011 (fig.3). For him, sneezing is a signal from the body about how things are going and an indicator of allergy triggers.

![]()

Fig.1. “Food tracking examples”, courtesy of Thomas Blomseth Christiansen

![]()

Fig.2. “Eczema tracking examples”, courtesy of Thomas Blomseth Christiansen

Fig.3. “Sneezes 2011-2016: Heatmap of daily count”, courtesy of Thomas Blomseth Christiansen

As with many other members of the Quantified Self, the desire to embrace self-tracking practices stems from a need to find solutions to health issues or life problems as well as a dissatisfaction with the generic top-down approach of mainstream medicine: I didn’t get any good solutions in the medical system […] The things that the medical system was telling me didn’t have the specificity relating to my life, and my circumstances, and that was why I could see this idea of collecting data from my daily living made sense.’ (Thomas interview, 2017). Thomas’ statement resonates with Gadamer’s arguments regarding the limitations of the medical field and the neglect of the personal dimension that even recent attempts and developments in “personalised medicine” have not yet managed to overcome (Vogt and Green, 2020). For Gadamer, science, including medical science, is ‘essentially incomplete’ (Gadamer, 1996: 4). Part of that incompleteness has to do with science’s inability to fully fathom the irreducible singularity of the person and the way modern science collapses the distinction between techne and praxis, i.e. between the technical application of rules and ordinary life practice. For, as mentioned before, science is primarily focused on reproducible structures and generalisable laws rather than the minutia of the personal and the humble layer of everyday experience. But ‘it is right to assert that medicine […] cannot do without the singularity of the patient in a sense utterly unknown to the natural sciences’ (Buzzoni in Abettan, 2016: 427). Hence the potential of personal science to complement the epistemological and methodological framework of medical science.

As opposed to the generalising and impersonal approach of mainstream medicine, Thomas believes that self-tracking provides the means to understand one’s body and health in a way that is more specific and amenable to generating tailored solutions that are suited to the needs of the person herself. For him, it is not so much a matter of who has the most knowledge but whether he believes in the methods applied: ‘When my allergies were getting worse and I went to my doctor, I was treated nicely. However, I didn’t experience the kind of problem-solving approach that I believe in […] that was when I decided I believe I have a better method for solving my personal health issues, my allergies, than the medical system’ (Thomas interview, 2017). Thomas takes issue with how medicine applies “general methods” to “personal problems” and often merely addresses the symptoms rather than the root causes: ‘Biomedicine wants to generalise interventions where I, as you know, want to find something that works for me’ (Thomas interview, 2021). Thomas managed, indeed, to succeed where his doctors failed. By taking matters into his own hands through self-tracking and finding “his own way” (Gadamer, 1996), he was able to rid himself of his allergies and find solutions to other health issues. In fact, he has not seen his doctor since 2008. Even during the current Covid-19 pandemic, and him suffering for months from what he suspected to be “long Covid-19” symptoms, Thomas decided not to visit his doctor nor rely on the healthcare system: ‘I haven’t felt confident about the countermeasures that they have been implementing […] I could potentially have gone to a doctor in March but I didn’t dare do it, because I thought that if I didn’t have Covid already, it might have been a big risk of contracting it by engaging with the healthcare system. So no, I haven’t seen a doctor since 2008’ (Thomas interview, 2021).

In his review essay on Gadamer’s The Enigma of Health, Dallmayr (2000: 330) argues that despite the deep infiltration of the everyday by scientific methods (Big Data and Artificial Intelligence being the latest examples), the ‘life-world remains an arena of practical involvement and engagement and the task which falls on all human beings is to “find our own way” in that world’. He continues to explain, following from Gadamer, that the task of finding one’s way in the life-world requires ‘not so much the technical application of rules as the exercise and cultivation of practical judgment—a faculty which today is greatly endangered. While the capacity for scientific and technical rationality is celebrated and continuously refined, the “autonomous formation of judgment and of action” is correspondingly neglected.’ (ibid.). This is in the sense that, for Gadamer, the more rationalisation, standardisation and objectification is applied, the more risk there is to the exercise of practical judgement informed by personal experience rather than generalised rules. Long before Gadamer, Kant himself bemoaned the reliance on external actors (human and technological) and the outsourcing of one’s judgement. He writes:

“Have courage to use your own understanding! Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why such a large proportion of men, even when nature has long emancipated them from alien guidance (naturaliter maiorennes), nevertheless gladly remain immature for life […] It is so convenient to be immature! If I have a book to have understanding in place of me, a spiritual adviser to have a conscience for me, a doctor to judge my diet for me, and so on, I need not make any efforts at all. I need not think, so long as I can pay; others will soon enough take the tiresome job over for me.” (Kant, 1784)

Such arguments are reminiscent of the current concerns raised vis-à-vis Artificial Intelligence and algorithmic governance where fears have been expressed about the danger of devolving responsibility and decision making to machines. This is what Zerilli et al. (2019: 555) refer to as “the control problem” which they understand as ‘the tendency of the human within a human-machine control loop to become complacent, over-reliant or unduly diffident when faced with the outputs of a reliable autonomous system.’ From such postulations arise some pertinent questions regarding the context of self-tracking: does self-tracking enable the exercise and cultivation of praxis (life practice) rather than merely the techne (technical application of rules)? And does self-tracking lead to autonomous formation of judgment and the reclaiming of agency and control over one’s health, or is it merely an act of delegating, if not even, outsourcing decision-making about life and health to technology itself?

One way of addressing these questions is to be found in the question of autonomy itself which holds a central position in both Western philosophy and in recent debates on healthcare developments and the role of patients. Autonomy also features prominently in the discussions on personal science given its focus on self-knowledge and self-reliance. Being one of the “four pillars” of medical ethics , autonomy entails the idea of self-governance and the right of individuals to make decisions about their healthcare and treatment options (including the right to not pursue the prescribed treatment). In the past, doctors made all the decisions for their patients in terms of care plan and treatment solutions. But there has been an increasing call, in recent years, to involve patients more in treatment decisions and create collaborative and active alliances between doctors and patients. Especially with the rise of digital health technologies and relevant online platforms, patients can now access health information with relatively more ease and act on this information with or without the assistance of their physicians. Autonomy also entails the twin concept of empowerment which serves as ‘a contrasting foil for medical paternalism’ (Shmietow and Marckmann, 2019: 627).

Critics, however, argue that what is often promoted as autonomy and empowerment in the current neoliberal age, is sometimes nothing other than a form of abandonment, as individuals are increasingly being left to their own devices (literally in this case) when it comes to healthcare issues, while state support is in a sharp decline. Hampshire et al. (2015), for instance, discuss the need for a person to have ‘digital capital’, that is to say, appropriate resources, social networks and skills, in order to access digitally-mediated healthcare. Similarly, Shmietow and Marckmann (2019: 626) argue that ‘[t]he reasonable use of digital health technologies such as self-tracking and self-management […] requires autonomy both in the sense of digital and health literacy. The user is not acting autonomously merely in the original sense of medical ethics as being able to consent to a specific treatment but on the basis of her self-learned competencies and with the support of customised, ubiquitous technology proactively takes charge of her (self-)care and prevention.’ But for those who lack digital capital, empowerment may feel much like abandonment. As Lucas (2015) points out, the responsibility of being involved in treatment decisions may be seen as just one more burden to carry, especially for poor individuals with a serious illness. The bottom line is that most patients would rather be cured than empowered, according to Lucas. What is at issue here is not only the difference between those who have digital capital and those who do not, but the amount of effort, resources and dedication one is willing and able to pour into digital health self-management, including self-tracking practices. This is also key to understating the difference between a dedicated member of the Quantified Self who has the time, energy and financial resources to invest into the tracking journey, as is the case of Thomas, and the mainstream amateur self-tracker who only casually, and mostly passively, engages in tracking practices through commercial apps and devices. Autonomy, as such, should not be seen as an absolute homogenous value, but ought to be regarded in a relation to the wider context of socio-economics, digital literacy and technical capital.

Thomas, like many members of the Quantified Self, has the added advantage of being able to build his own tracking tools, which enables him to gain autonomy vis-à-vis how his tracking data are handled and stored, and overcome reliance and dependency on commercially available tracking products. In 2011, he developed, along with digital innovators, Mette Dyhrberg and Klaus Silberbauer, the smartphone app, Mymee (fig.4), which can detect non-obvious correlations between symptom patterns and daily behaviours. Mymee tracks fluctuations in symptoms and lifestyle variables including food and fluid intake, sleep, activity patterns, environmental exposures and many other biometrics. The autonomy-enabling part of this app lies in its flexible design. Unlike mainstream tracking apps, Mymee does not come with pre-determined fixed variables that users must track, but allows the user instead to determine, alone or with the help of doctors, which variables are most important to track based on symptoms and health background. The variables can also be added, modified or subtracted at any time (Goldman, 2014). In addition to Mymee, Thomas has also developed an app to track his running (fig.5) and a one-button instrument he uses to track itching in his nose (fig.6).

Fig.4. “Mymee app 2011”, courtesy of Thomas Blomseth Christiansen

![]()

Fig.5. “GUIDO app developed for tracking running”, courtesy of Thomas Blomseth Christiansen

![]()

Fig.6. “One Button Tracker v0 used for tracking itching in nose since 2018 developed with Jakob Eg Larsen”, courtesy of Thomas Blomseth Christiansen

As Christiansen, Kristensen and Larsen (2018: 106) point out, citing several examples, building one’s instrumentation is not an unusual practice among experienced self-trackers. They argue that, in doing so, the self-tracking experience becomes an empowering journey of discovery and experimentation as ‘the self-tracker is transformed from being an object, a source of data and/or patient to a self-efficacious subject actively reflecting on, acting and taking charge of their own health and well-being.’ (ibid.: 111). For building one’s own tracking tools or modifying existing ones enables the self-tracker to overcome the limitations and assumptions inherent in commercial products. As the authors explain further, the design of commercial products is mostly based on a set of presumptions about the mode of use and interactions with data: ‘It is typically the case that the vendor has decided on behalf of the user how the collected data are analysed and presented which limits the set of questions the user can seek answers to and ultimately if they are able to validate or reject their hypotheses.’ (ibid.: 113).

But despite the seemingly autonomy-enhancing benefits of Quantified Self practices, the question still remains as to whether self-tracking helps cultivating praxis and truly reclaiming agency over one’s health and wellbeing. At issue here is the role and status of technology itself in the self-tracking process. The relationship between autonomy and technology is, in fact, as old as technology itself and has been a major preoccupation for philosophy. As De Cesaris (forthcoming) points out, Plato’s critique of the technology of writing, for instance, can be understood as ‘a critique of how the delegation of memory to an external device […] makes us subject to that device itself […] Those who confide in external devices in order to remember are no longer autonomous.’ In this sense, one can argue that, in the context of the Quantified Self, even the most techno-savvy self-trackers are not truly autonomous as they still have to rely on tools and instrumentation (even if it is just the basic pen and paper) to collect, record and analyse data. And even when self-built, the technological affordances of the devices and apps still delimit what is possible and what is not vis-à-vis the tracking experience and the degree of self-knowledge that could be achieved. Yet, when seen through the lens of Kant’s earlier quoted statement, the fact that the self-tracker does not have to a rely on ‘a doctor to judge her diet for her’, as is the case with Thomas, can in itself be regarded as an autonomy-affirming aspect. De Cesaris captured a similar paradox by arguing that, on the one hand, self-tracking ‘allows a form of disintermediation, thanks to which the subject finally becomes fully autonomous and capable of doing by himself all that is required in order to live in society, instead of confiding in experts.’ (De Cesaris, forthcoming). But on the other hand, ‘using tracking devices is a way of delegating to an artefact an activity that should be executed by us […] Ironically, there is no “self” in self-tracking, and the name associated with the phenomenon betrays the ideological attempt to conceal a very simple truth: thanks to our devices, we stop being subjects.’ (ibid). These two opposing interpretations are based, according to De Cesaris, on two different understandings of technology: the first being that of technology as practice. The second being that of technology as a device. While the former implies praxis and competence of which Gadamer speaks, the latter is more instrumental and tool-driven.

To be sure, when it comes to self-tracking, these two opposing approaches are not necessarily antithetical but co-exist within the tracking experience. This is something that is highlighted in Thomas’ answer to the question concerning autonomy and what he refers to as “epistemic agency”:

” You have your own epistemic agency, you can figure stuff out, and you don’t have to ask for permission from anybody, or any institution to figure stuff out. I think that’s the core of autonomy. A lot of things follow from giving yourself epistemic agency […] I think so much of the technology I’m using is instrumentation. In that sense, that’s where there’s potentially several historical analogies between personal science, and then the emergence of other new sciences. You get some new instrumentation, and that means that you can engage with yourself in new ways. I don’t see that as something that’s soaking up all the agency. I see it the other way around, it’s more like musical instruments, where my musical expression is made possible by the clarinet. It’s not that the clarinet owns it […] Of course, there’re some things I couldn’t do without it, but there’re also things I would never have thought about doing or being able to do without the instrumentation.” (Thomas interview, 2021)

From here we can gather some interesting conclusions about the role and status of technology, which point to the complex relationship between technology and the subject of self-tracking that goes beyond the oppositions of technology-as-practice and technology-as-device. The analogy Thomas draws between self-tracking instruments and music instruments elucidates how technology is more than just a tool that can be put to use by human actors, but it also provides the conditions of possibility for ways of thinking and doing that would not be otherwise conceivable. Agency, in this sense, is not wholly human nor wholly technological. It is a hybrid agency, shared between the subject of tracking and technology. So, perhaps, in this sense, autonomy comes from the fact that self-trackers reclaim some of the agency from biomedical expertise and the like only to share it with their own practices, their own technologies and methods, and their own community of practice, with which they are constantly co-evolving. Absolute autonomy is “a myth,” as De Cesaris puts it, since it is impossible to conceive of the subject outside the mediated constellations of relations it shares with its environment.

What springs to mind here is also Heidegger’s reflections on the essence of technology. In his famous essay, The Question Concerning Technology, Heidegger (1977) argues against a reductionist view on technology which confines its definitions to either the instrumental approach (technology as a tool) or the anthropological approach (technology as a human activity). Instead, he argues that the essence of technology lies primarily in its revealing and enframing capacities. As Thomas indicates through the metaphor of the clarinet, technology allows forms of expression and practices which, in turn, can reveal one’s talent, capabilities, limitations, areas of improvement, and so on. Technology also, and increasingly so, frames the way we understand, govern and relate to the world. As is evident throughout the above discussion, biometric self-tracking techniques are increasingly providing the lens through which the user can view, assess and act on the body and everyday life. For Heidegger, there is the danger, however, that the revealing and enframing functions of technology renders everything, including humans, as a standing-reserve:

“Everywhere everything is ordered to stand by, to be immediately on hand, indeed to stand there just so that it may be on call for a further ordering. Whatever is ordered about in this way has its own standing. We call it the standing-reserve […] As soon as what is unconcealed no longer concerns man even as object, but does so, rather, exclusively as standing-reserve, and man in the midst of objectlessness is nothing but the orderer of the standing-reserve, then he comes to the very brink of a precipitous fall; that is, he comes to the point where he himself will have to be taken as standing-reserve.” (Heidegger, 1977: 17, 27)

We can see such danger manifesting in the way self-tracking data can be exploited for surveillance and commercial ends and repurposed beyond the self-tracker’s initial aims of learning and self-knowledge, especially when data are shared on social media and other platforms, and stored on vendors’ cloud storage systems. Such issues have been the subject of much debate in academic literature, drawing attention to the privacy issues raised by self-tracking practices as well as the extractionist and exploitative aspects of data use by companies (see for instance Ajana 2017, 2018, 2021; Moore and Robinson, 2016; Whitson, 2013; Sanders, 2017; Lupton, 2016; Timan and Albrechtslund, 2018; Charitsis, 2019; Till, 2019). Thomas is very protective over his “raw data” and only ever shares his interpretations and analyses of that data: ‘As a technologist, I know that if you share your raw data on the internet, then it’s out there, and you can never retract it, and you can’t know what it might be used for. So, of course, one of the basic measures is not to share your raw data out in the open.’ (Thomas interview, 2017). For Thomas, the danger is not only the risk of data exploitation and commercialisation, but also the hindering of the learning process itself which is the core of the Quantified Self:

“I believe that other entities, institutions, for instance, like corporate wellness schemes, or health insurers, shouldn’t have access to the raw data […] if they have access to the raw data, it might pervert the self-tracking process, and it might introduce bad incentives, and what we want to foster with the self-tracking process is a learning process where the individual discovers things about herself that’s important to her, and if you have these institutions collecting the raw data, then you might not get self-tracking that’s reliable or useful, not even to the person that’s doing the self-tracking […] I think an arm’s length principle is a good idea.” (Thomas interview, 2017)

One may still quibble about whether Quantified Self practices, such as those of Thomas, also end up rendering the body as a standing-reserve and objectifying its ontology? This also begs the question as to how the body is perceived and treated in the Quantified Self in the first place. In the case of Thomas, he often invokes the notion of ‘debugging’ when describing his self-tracking practices and perception of his body:

“I wanted to debug myself, as I know from debugging a computer system […] So, in that sense, you could say that I’m looking at myself as a system, but I also know that I’m a very complex adaptive system, that I can’t kind of coerce my biology into doing things, I have to kind of work with it, and that was also one of the things that I really didn’t believe in about the current [medical] treatment for allergies. It’s that you’re actually trying to just dampen the system instead of working with the body, and then taking the signals, or the signs that the body’s providing seriously, and then trying to work from there […] If you really want to improve the system, you have to work with the system, and figure out what are the deep mechanisms at play.” (Thomas interview, 2017)

While treating the body as a system can be perceived as a form of objectification that reduces the body to a machine metaphor and an information dispenser, the opposite can also be said in terms of how this system thinking encourages the self-tracker to work with the body (body as subject) instead of just on the body (body as object), to work with biology rather than despite of or against biology. The body in this sense is not just an entity to be tracked, measured and controlled but it is a revealing agent that is capable of incorporating technologies and practices so much so that, at times, it is difficult to establish ‘where the body starts and technology ends’ (De Stefano, forthcoming). As such, and at least in the self-tracking context, it is perhaps futile to seek to sperate between body and technology since they are co-constitutive of each other. And just as Socrates differentiates between good and bad writing practices in terms passive and active forms of remembrance, one can also differentiate between bad and good self-tracking practices. Bad self-tracking can be described as the passive practices which objectify the body and conform to the standards and categories determined by technology companies. As Diaz-Bone (2021: 305) argues, often the categories and algorithms are encoded and implemented by companies themselves and the resulting data are rarely controlled by users or adapted to their health situation. As opposed to that, good self-tracking is that which entails the user’s active involvement in the design and implementation of the tracking solutions as well as a total transparency of the underlying measurement conventions and how they are decided. Again, this is what differentiates between members of the Quantified Self circle who build their own tracking tools and the general users who rely on the commercial tracking products available on the market. This difference, according to De Cesaris (forthcoming), can also be expressed as ‘the opposition between an active and a passive relation with design.’ Therefore, it can be argued that design is ethics and the task is to nurture a critical and inclusive approach to technological development whereby users can be involved in the means of production and become experts rather than just users.

It is in this sense that the Quantified Self community can act as a “guru” for mainstream self-trackers. This is not only in terms of the way members of this community have been the vanguard of self-tracking before the practice became commercialised and widespread in society, but also given their epistemic and technical skills that can be shared beyond the confines of this niche community. For instance, through the organisation of practical public events such as design boot camps and hackathons, and the development of modular tracking tools at a wider scale, the Quantified Self community can impart its knowledge and savoir-faire to the general public in order to educate users on how to build their own personalised tools or adapt commercial ones to suit their specific needs, and how to protect their privacy and data from function creep (data repurposing) and commercialisation. This, in fact, seems the direction towards which the Quantified Self community is currently heading, according to Thomas. While Thomas does not refer to himself as a guru per se, he is committed to inspiring others and sharing his expertise by participating in conferences and delivering public talks, collaborating with academics and tool developers, and most importantly for him, providing a counter-narrative to the commercial hype currently surrounding self-tracking practices. It is utterly important for him to demonstrate, through his experience, that self-tracking is about developing and adopting methods and ways of thinking that commercial tools do not necessarily provide. When he was asked about whether he saw a risk that the Quantified Self community might eventually slip into commercialising ethos, he replied with the following:

“I don’t think it will slip because it went into some kind of a slow burn […] there has been a core of the community that had then just carried on working on this stuff. Then, the commercial interests have retracted from the community because they don’t see it as really a way of marketing stuff. Gary Wolf has also been protective [and] he can very quickly snuff out that what they really want to is to see if there’s some access to a market here. He’s been protecting the community from that […] It’s the learning and that sharing of methods around how you do things that’s been front and center, and that’s not necessarily very compatible with the more commercial interest. I think it’s pretty resilient to that kind of influence but, of course, it’s also limited in its impact and that’s what we’re working on. It’s limited in the sense that the knowledge around the practice is not easily accessible to people outside the community […] That’s where we are becoming a bit more activist, in some sense. Hopefully, we can take all that learning and distill it into a form that will appeal to a broader audience, that’s the goal.” (Thomas interview, 2021)

So, it remains to be seen whether this niche community of practice will be capable of reaching out to wider publics and reconfiguring self-tracking beyond commercial interest and institutional control on a wider scale.

References

Abettan, C. (2016) ‘Between hype and hope: What is really at stake with personalized medicine?’, Medical Health Care and Philosophy, vol. 19, pp: 423-430.

Ajana, B. (2017) ‘Digital health and the biopolitics of the Quantified Self’, Digital Health, vol.3 (1), pp: 1–18.

Ajana, B. (ed.) (2018) Metric Culture: Ontologies of Self-Tracking Practices, Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

Ajana, B. (2020) ‘Personal metrics: Users’ experiences and perceptions of self-tracking practices and data’, Social Science Information, vol.59 (4), pp: 654-678.

Ajana, B., Braga, J. and Guidi, S. (eds.) (forthcoming) The Quantification of Bodies in Health: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

Canguilhem, G. (1991) The normal and the pathological, New York: Zone Books.

Charitsis, V. (2019) ‘Survival of the (data) fit: Self-surveillance, corporate wellness, and the platformization of healthcare’, Surveillance & Society, vol.17 (1/2), pp: 139–144.

Christiansen, T.B., Kristensen, D., and Larsen, J.E. (2018) ‘The 1-Person Laboratory of the Quantified Self Community’, in: Ajana, B. (2018) Metric Culture: Ontologies of Self-Tracking Practices, Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

Dallmayr, F. (2000) ‘The Enigma of Health:” Hans-Georg Gadamer at 100’, The Review of Politics, vol.62 (2), pp: 327-350.

De Cesaris. A. (forthcoming) ‘Quantified Care: Self-Tracking as a Technology of the Subject’, in: Ajana, B., Braga, J. and Guidi, S. (eds.) The Quantification of Bodies in Health: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

De Stefano, L. (forthcoming) ‘I Quantify, Therefore I Am: Quantified Self Between Hermeneutics of Self and Transparency’, in: Ajana, B., Braga, J. and Guidi, S. (eds.) The Quantification of Bodies in Health: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

Diaz-Bone, R. (2021) ‘Economics of Convention Meets Canguilhem’, Historical Social Research, vol.46 (1), pp: 285-311.

Gadamer, H-G. (1996) The Enigma of Health: The Art of Healing in a Scientific Age, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Goldman, E. (2014) Mymee App Reveals Disease Clues Hidden in Daily Life, available at: https://holisticprimarycare.net/topics/practice-development/mymee-app-reveals-disease-clues-hidden-in-daily-life/

Hampshire, K., Porter, G., Owusu, S.A., et al. (2015) ‘Informal m-health: How are young people using mobile phones to bridge healthcare gaps in Sub-Saharan Africa?’, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 142, pp: 90–99.

Heidegger, M. (1977) The Question Concerning Technology and Others Essays, New York: Garland Publishing.

Heyen, N.B. (2020) ‘From self-tracking to self-expertise: The production of self-related knowledge by doing personal science’, Public Understanding of Science, vol.29 (2), pp: 124-138.

Lucas, H. (2015) ‘New technology and illness self-management: Potential relevance for resource-poor populations in Asia’, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 145, pp: 145–153.

Lupton, D. (2016) ‘The diverse domains of quantified selves: Self-tracking modes and dataveillance’, Economy and Society, vol. 45(1), pp: 101–122.

Jethani, S. and Raydan, N. (2015) ‘Forming Persona Through Metrics: Can We Think Freely In The Shadow Of Our Data?, Persona Studies, vol.1 (1), pp: 76-93.

Keane, N. (2015) ‘On the Origins of Illness and the Hiddenness of Health: A Hermeneutic Approach to the History of a Problem’, in: Meacham, D. (ed), Medicine and Society, New Perspectives in Continental Philosophy, London: Springer.

Kant. E. (1784) ‘An Answer to the Question: “What is Enlightenment?”’, available at: https://www3.nd.edu/~afreddos/courses/439/what-is-enlightenment.htm

Martin, B. and Brouwer, W. (1991) ‘The Sharing of Personal Science and the Narrative Element in Science Education, Science Education, vol.75 (6), pp: 707-722.

Martin, B., and Brouwer, W. (1993) ‘Exploring personal science’. Science Education, vol.77 (2), pp: 235–258.

Moore, P. and Robinson, A. (2016) ‘The quantified self: What counts in the neoliberal workplace’, New Media & Society, vol.18 (11), pp: 2774–2792.

Piras, E.M. (2019) ‘Beyond self-tracking: Exploring and unpacking four emerging labels of patient data work’, Health Informatics Journal, vol.25 (3), pp: 598-607.

Sanders, R. (2017) ‘Self-tracking in the digital era: Biopower, patriarchy, and the new biometric body projects’, Body & Society, vol. 23(1), pp: 36–63.

Schmietow, B., Marckmann, G. (2019) ‘Mobile health ethics and the expanding role of autonomy’, Medical Health Care and Philosophy, vol. 22, pp: 623–630

Till, C. (2019) ‘Creating ‘automatic subjects’: Corporate wellness and self-tracking’, Health, vol. 23(4), pp: 418–435.

Timan, T., Albrechtslund, A. (2018) ‘Surveillance, self and smartphones: Tracking practices in the nightlife’, Science and Engineering Ethics, vol. 24, pp: 853–870.

Vogt, H. and Green, S. (2020) ‘Personalised Medicine: Problems of Translation into the Human Domain’, in: Mahr D. and von Arx M. (eds) De-Sequencing. Health, Technology and Society, Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Whitson, J.R. (2013) ‘Gaming the quantified self’, Surveillance and Society, vol. 11(1/2), pp: 163–176.

Wolf, G. (2010) The data-driven life. New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/02/magazine/02self-measurement-t.html?_r=0

Wolf, G.I. and De Groot, M. (2020) ‘A Conceptual Framework for Personal Science’, Frontiers in Computer Science, vol.2 (21), pp: 1-5.

Zerilli, J., Knott, A., Maclaurin, J., and Gavaghan, C. (2019) ‘Algorithmic Decision-Making and the Control Problem’, Minds and Machines, vol. 29, pp: 555-578.